Through the Tunnel, Home

Chapter 1

When the children whom they cared for were in the nursery fast asleep, Alice and Okey liked to sit on the side porch of the Meyer’s house, off the library, their legs dangling over the side. There were no chairs on the side porch, because it was just for firewood and the dog houses, which were made of bales of hay covered by blankets. Alice sat up straight on the edge of the porch and stared up at the stars as if she were displeased with them for remaining silent and mysterious and far away.

At the end of every workday, she felt like a martyr. She had given up her whole life to wrangling seven small people to be clean, decently behaved, occupied, and uninjured. Meanwhile, the whole world of intrigue, achievement, nature, art, politics, construction of new railroads, factories, and on and on and on, was conducted utterly without her input. Childcare, if you are of Alice’s cast of personality, is a sacrifice. It was never fun. The minutes and hours did not rush by. Her negotiation with six-year-old Aaron over sharing the toy train cars with his younger sister Rachel had felt tedious to Alice. All her joints now hurt, especially her neck. She knew she probably shouldn’t feel like a martyr and that some women might be filled with satisfaction, fulfillment, and even joy at the chance to spend all their days in a beautiful home (even if it belonged to her employers, the children’s parents) playing games and being adored by sweet young people. That just wasn’t Alice.

Alice’s husband Okey, on the other hand, spent his days doing what he would have chosen to do even if he didn’t have to earn a living doing it for the Meyers: planting and weeding and picking vegetables and flowers from their gardens, cutting back brush, mowing lawns, repairing broken furniture from the house, feeding and watering the animals (four dogs, three pigs, ten cows, five horses, and dozens of white chickens), and buying animal feed and other supplies from the market.

The dogs crawled into their straw bale houses at around nine every night, crossed their front paws, lowered their heads, and slept until dawn. And so it was to the sound of dogs softly snoring, crickets chirping, and bullfrogs croaking that Alice and Okey spent their evenings on the porch.

But some nights, they stole away from the Meyer house to sit at the mouth of the unfinished tunnel and stare into its black rock maw.

They brought with them a kerosene lantern though there was usually still some light at the edges of the sky. Decades later, the sweet smell of kerosene would remind them both of sitting by that tunnel feeling free. Behind them was a quiet creek and the occasional sound of a carthorse’s soft clip-clop along the dirt road. They took sips from a small bottle of bourbon. They kissed.

During the day, this place was crawling with dozens of men working to dig the tunnel. The sound of metal hitting stone rang out from sunrise to sunset as it had been doing for the past dozen years. None of the Meyer children were old enough to remember living in a world without the clatter of metal and the intermittent dynamite explosions.

But at night, the workers abandoned the cave. Their tools and machines lay on the ground overnight.

How far did the cavity extend into the mountain? A mile? Alice and Okey hadn’t yet got up the nerve to walk inside to see. A dank breath of cold air exhaled steadily out of the hole toward them. On the other side of the mountain, in North Adams, there was a corresponding hole being dug through identical solid rock, and at the center point of the two-peak mountain range, there was a deep, vertical hole that extended over 500 feet down into the mountain. This center well through the mountain would be the starting point for yet more digging: westward toward North Adams and eastward toward where Alice and Okey sat. Someday all these tunnels would meet and become one straight shot through the mountain. Then railroad track would be laid down, and pretty soon after that trains would roar through.

Alice liked to drink, only after work, and she’d brought a small bottle of port with her, which she tipped up every few minutes, leaning against her husband and staring at the starry sky.

“‘Nice tonight,” she said on a warm July night in 1867. The stars were ridiculously numerous in the wide sky. There were dustings and swaths of stars, and then every few inches—or billions of miles—a lone bold diamond of a star. Those, Alice thought, must be closer. Or the same distance away but larger?

“That’s about half the universe right there,” Okey said, squeezing his wife’s hard hand. He felt, usually, like a passenger on her ship. Alice—dark-skinned, tall, stern, and wound tight—could carry them all wherever she decided they should go. For instance, the only reason they had this job watching the Meyer’s seven children and doing work around the property was that Alice had struck up an acquaintance—you might say even a friendship— with Ingrid Meyer down at the river, at a swimming hole. It was in the evenings when they were outside by the tunnel that Okey remembered the world was as much his as it was Alice’s, as much theirs as it was the Meyers’s.

Sky and tunnel, two kinds of black mystery. Astronomers wouldn’t know about galaxies beyond the Milky Way for another thirty years, but when they did figure it out, and Okey read about the discovery in the newspaper, he would think back to these nights by the unfinished tunnel. He would marvel at how small a section of a universe made up of galaxy upon galaxy he’d actually been seeing.

The year before, fourteen men had died working on the tunnel. You couldn’t be a working man in this county and not feel guilty and lucky that you weren’t part of the tunnel crew.

Alice and Okey heard people talking nearby in the dark.

“What are they saying?” Alice whispered.

“Shhhh,” said Okey.

It was two or three men, they could tell that much. And the men were arguing, each making a strong case about something. Their voices were urgent rather than angry.

The Meyers’ house, which was built in high Victorian style, was the largest house Alice and Okey had ever been inside, and the most beautiful. Its entryway was all polished wood and high ceilings. On the second floor, there was a cavernous ballroom lit by an enormous crystal chandelier. In all, the house had twelve bedrooms. The large nursery where Alice spent much of her time with the children was made up of a central playroom with tall windows alternating with five doors that led to the children’s bedrooms and one black-and-white tiled bathroom with a tub and commode and a pale gray marble bench where Alice sat when the little children were in the bath. A child could drown in the blink of an eye, Alice knew. The best thing about the Meyers’ bathrooms was the faint, powdery smell of soap they all had in common, and the lace curtains and little blue glass bottles of rubbing alcohol, oils, and perfume.

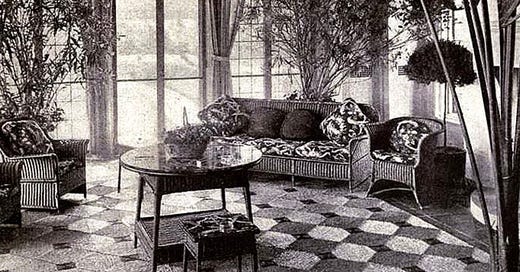

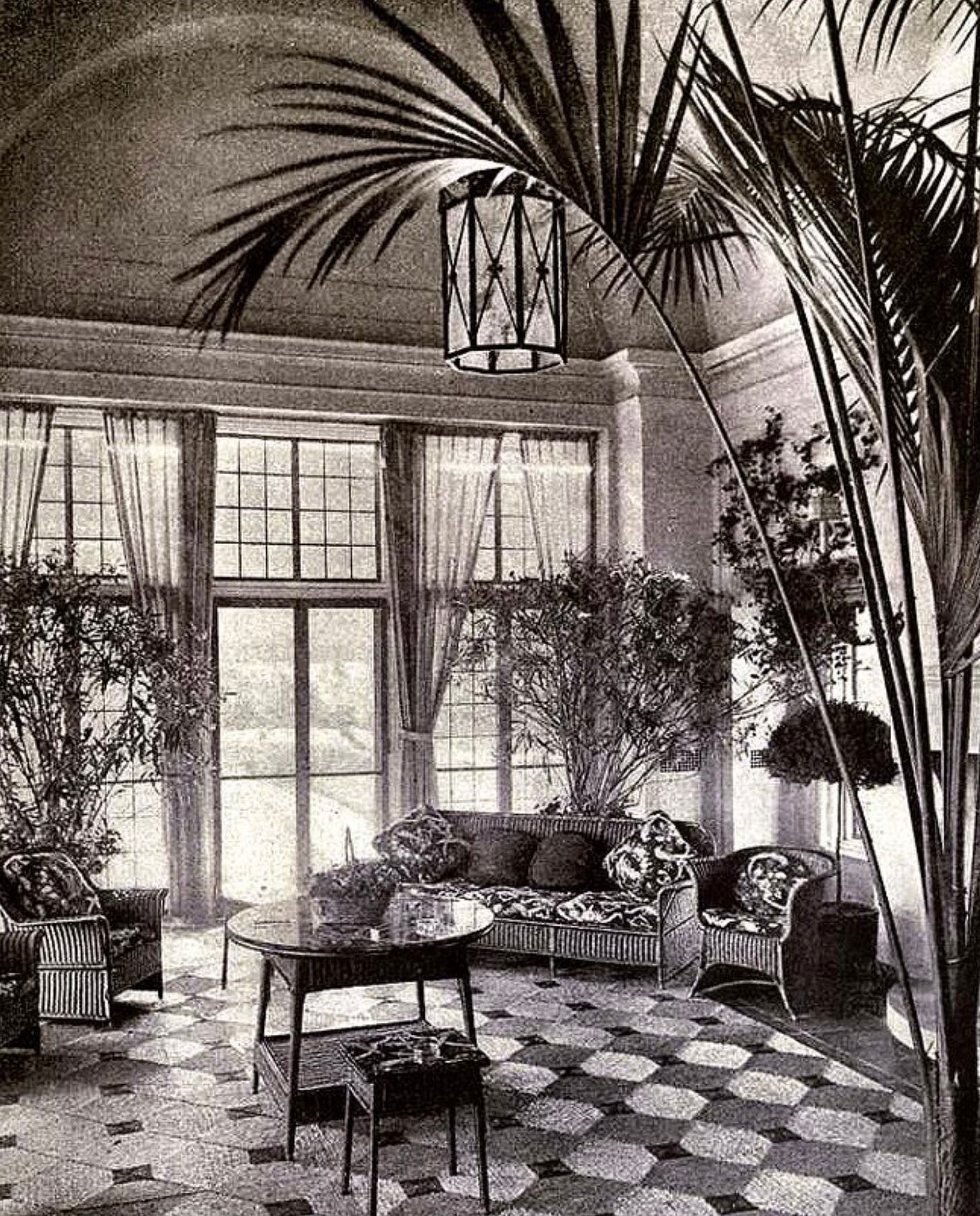

The house also had a solarium where Mrs. Meyer grew lemon and orange trees alongside a profusion of tropical flower species that reminded Okey of outlandish women’s hats. Stepping through the French doors into the solarium was like stepping into the Garden of Eden itself. There were birds living there, nesting in the corners of the ceiling on narrow ledges built there for that very purpose—wrens and sparrows and chickadees. Had a naked man wearing a fig leaf over his privates emerged from behind a hibiscus tree, Alice would not have been surprised.

When they’d first been hired, Alice had found the house imposing. Everything exceptional about it was a constant reminder of how much richer some people were than others, and how much more white people had than black people did. She felt no possibility of herself ever being rich enough to have a home so hushed and gleaming, so mild in spirit and grand in looks that it enveloped its inhabitants in a comforting embrace that promised beauty and comfort at every turn.

But the longer she and Okey stayed and the more at home they began to feel, the more Alice started to think of the Meyer house as her own. Or, if not her possession, her ally. Those long halls lined with elegant chairs and mirrors and paintings on the walls were right for her. The rose damask silk settee in the sitting room on the first floor was a perfect reflection of her own taste. What she appreciated belonged to her, in a way. Isn’t that the power of appreciation?

It is true that it was unusual in those days in the American north for a married couple to share as live-in help the care of another couple’s children, but the Meyers were Germans immigrants and Transcendentalists.

“If we only had two or three,” Jean Meyer was telling her older sister Rose, who was visiting from Boston, “I probably wouldn’t need any help, really.”

“I suppose it’s been so long since you’ve had only two babies to remember what it was like,” Rose said. Rose was secretly horrified by how many children her younger sister had birthed. It just kept happening.

Alice rapped lightly on the door frame.

“Oh, Alice, hello!” Jean called out, waving her forward. “Come sit, come sit.”

This was in Massachusetts, less than a year after the end of the Civil War. It was rude of Jean to ask Alice to sit down like a guest in the home she worked in. It was rude to both Alice and to Rose visiting from Boston. But Jean Meyer was like that. She was always forgetting how things were supposed to be done.

Alice sat on the edge of the chair and with her hands crossed primly like a sleeping dog’s. Unlike the dogs though, she was alert to danger and ready to jump up gracefully at the slightest hint that she could do so without offending Mrs. Meyer.

“How are the children today? Do they know that their Aunt Rose is up and ready to see them?”

Alice leapt up and said unsmilingly, “Let me go get them now if you like?”

“Well, I suppose now is as good a time as any,” Mrs. Meyer said, flapping her hand in the air and looking at Rose rather than at Alice.

The seven Meyer children ranged in age from four to thirteen. They were intelligent children, each so different in character and looks from all the others that Alice and Okey wondered if some or all might be adopted. Helena was a witty girl, an arresting beauty with a cloud of black hair and very pale skin. Just ten years old, she had already settled on a preference for speaking in deadpan tones, her face bored looking. She did this to be funny, Alice guessed.

“John has gone missing. Whatever shall we do?” Helena would say, “He’s probably been eaten by a wolf.” But John would be sitting right next to her reading a history book. Helena was a good elder sister to John, who would talk for minutes without pause if you let him, about whatever he was reading at the time—the history of the American Indian in the West, the history of shipbuilding, the history of Germany …

Where John was talkative, his brother Charles was painfully shy and almost never said a word. Where Helena was witty, her sister Velma was humorless and overemotional. She cried nearly every day over one thing or another. She was, to be certain, Alice’s least favorite charge.

“If I were you,” Mrs. Meyer had said to Alice early one recent morning when they were both in the basement kitchens—Alice to prepare a breakfast for the children, Mrs. Meyer to find a pot of jam. She had a craving for one spoonful of strawberry jam.

“If I were you,” Mrs. Meyer said, “I would clean ignore Velma and her tantrums. We must break her of the habit of bursting into tears every minute.”

But Alice had no idea how to ignore a wailing child, as much as she’d like to. And she didn’t think that Velma would ever stop taking every little thing to heart, even if they were somehow able to get her to stop crying so easily.

“Something happened to that child,” Alice said to Okey more than once. “Or her room is haunted or something.”

“Time to go see your Aunt Rose, children,” Alice announced loudly from the door to the nursery. “Now. Get up, get up. Let’s go.”

To be continued.

Just another amazing, can't stop reading, beginning... How do you do it?!!

By the way, it was really annoying to have to be authenticated just to write that comment!

You’re clearly on your way to something here. More of this character too please!